Cognitive scientist Daniel Willingham: Teachers tell me my book has changed their practice for better

His book was dubbed by The Washington Post „a triumph of critical thinking“. Since cognitive science offers ways of thinking about children’s learning, motivation, and emotion that have proven useful, experts recommend Why Don’t Students Like School? to both teachers and parents, particularly those home-schooling their own children. Once you start reading, you will find that Professor Daniel Willingham explains complex topics in the most accessible way. Why Don’t Students Like School? is now out in Czech, presented by EDUkační LABoratoř in cooperation with publishED. At this occasion, we have asked the author several questions.

CZ: Kognitivní psycholog Willingham: Učitelé mi píšou, že moje kniha změnila jejich praxi k lepšímu

How were your school years?

It varied a lot depending on my teacher and friends that year. I usually didn’t like school that much, until college.

Can we expect all pupils to like school?

“Expect the worst, hope for the best!” Certainly we should try to make every student think that school is worthwhile. That’s different than enjoyable—we all engage in activities that are challenging and at times frustrating, but we feel pleasure in accomplishment.

Daniel T. Willingham earned his B.A. degree in psychology from Duke University in 1983 and his Ph.D. degree in cognitive psychology from Harvard University in 1990. He is currently professor of psychology at the University of Virginia, where he has taught since 1992. He is the author of several books, and his writing on education has appeared in 17 languages. In 2017 President Obama appointed him to the National Board for Education Sciences. // Photo: DTW archive

You are a cognitive scientist. How would you explain this term to a teacher who has never heard it before?

Cognitive science is the study of the mind. It brings together research techniques and findings from several disciplines, including psychology, neuroscience, philosophy, anthropology and computer science.

How vital is it for every teacher to know the principles that cognitive science helps to unveil? Can you be an excellent teacher even if you lack this knowledge?

I do think it can be a great help. Teachers inevitably have a model in their minds of how children learn, what motivates them, what their emotional lives are like. It’s based on this model of the mind that teachers react in the moment to situations in the classroom. Research can offer new ways of thinking about learning, motivation, and emotion that have proven useful.

What outstanding practice would you like to see in every school? Could Michaela Community School in London, whose teaching is based on the findings of cognitive science, serve as an example? Some critics have called it a factory for learning.

I don’t know enough about Michaela to comment on it in particular, but I will say I think there are many ways to organize a school and a classroom that are aligned with principles from cognitive science. I’m fond of drawing an analogy to architecture. If you don’t follow the principles of physics and materials science when you design a building, it won’t stand. But physics and materials science don’t tell you what the building should look like, it’s size, the materials you use, and so on. In the same way, cognitive science lays out some very broad principles to make learning successful, but it doesn’t prescribe one method of instruction.

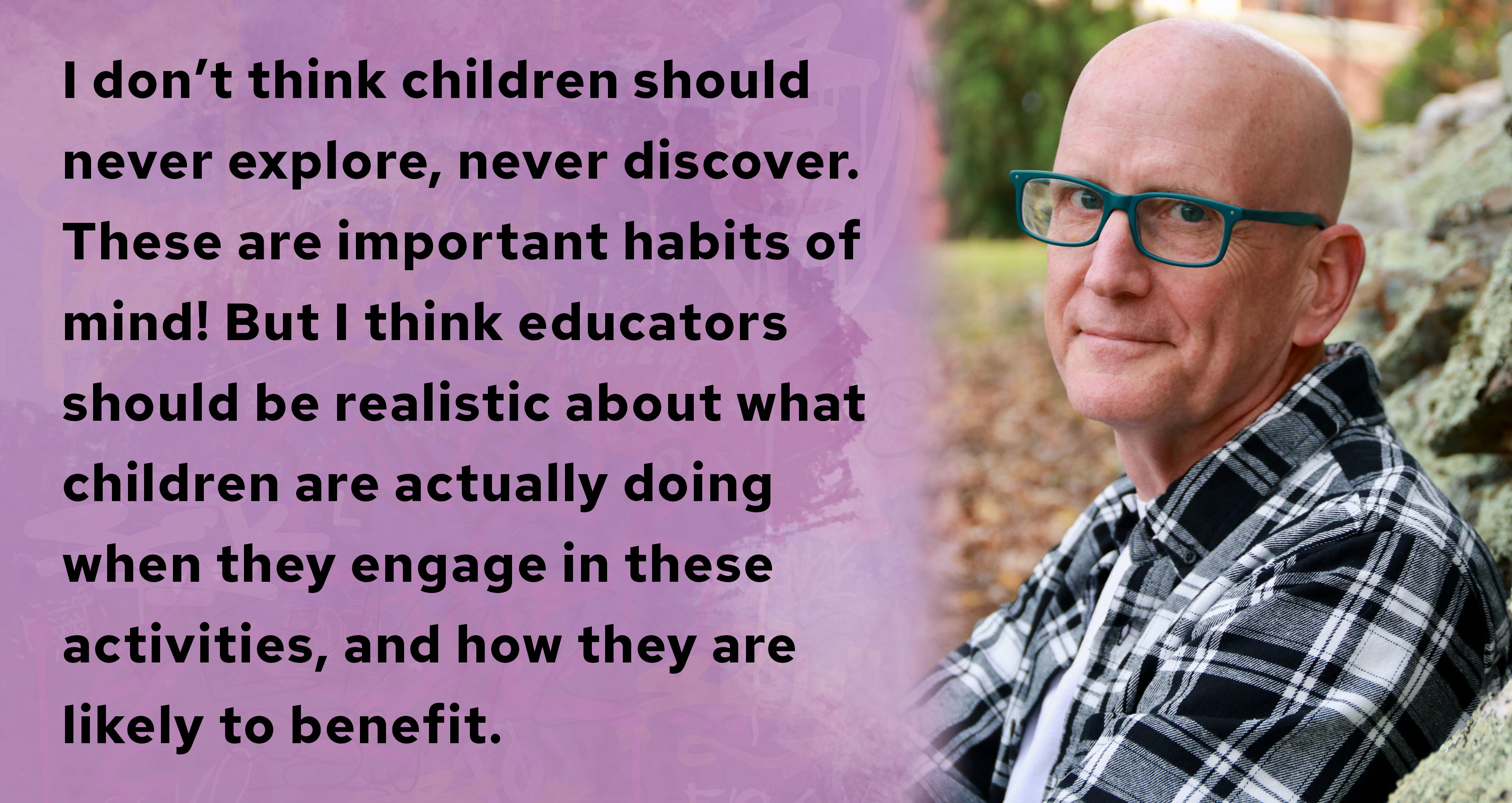

Discovery learning has become a stable element of the Czech education landscape. Some teachers have been working hard to implement it in their practice. However, you claim that trying to get pupils to think like scientists is not a realistic goal, since pupils are no experts, but novices, and therefore the way they think is fundamentally different. Can discovery learning be designed in a way that is in line with the findings of cognitive science?

I don’t think children should never explore, never discover. These are important habits of mind! But I think educators should be realistic about what children are actually doing when they engage in these activities, and how they are likely to benefit. And what it will take for the teacher to shape the lesson plan in a way that students will gain the benefit the teacher hopes for.

Photo: DTW archive, graphics: EDU

Why should teachers learn about human cognitive architecture in an era that is marked by the advent of artificial intelligence? AI represents a novel form of thinking, liberated from the boundaries of the human brain. Could it revolutionize education to an extent that cognitive science becomes obsolete?

I’m not much of a futurist. In the relatively short time I’ve studied education—about 20 years—I’ve heard of at least a half dozen technologies that were supposed to completely change everything. None of them have, and so I’m leery of claims that AI will do so now. Obviously teachers must think of ways students might access AI in ways that won’t ultimately harm their education, as well as try to think creatively about ways it might enhance it.

You wrote: „It is never smart to tell a child that she’s smart. Believe it or not, doing so makes her less smart. Really.“ Could you elaborate on that? Does it apply to parents as well? And what message does your book convey to them?

Well, there’s a whole chapter on this topic in the book, so it’s hard to be brief. It’s a reference to work on attribution, especially work by Carol Dweck, showing that it’s not optimal for children (or adults) to think that their success in thinking is due to an inborn quality—intelligence. It’s much better if they think that success comes from persistence and hard work.

Your book has become a world-wide bestseller. Can you think of any feedback that took you by surprise in either way?

I’m very pleased, of course, that the book has been as widely read as it has. Occasionally someone will offer a kind of quirky criticism, but much more often I get emails from teachers telling me I changed their practice for the better.

Is there any final thought you would like to share with your prospective Czech readers?

I hope you feel about my book the way your students feel about school: that you enjoy it, that it challenges you, and that it makes a little change in you!

Rozhovor vznikl ve spolupráci s Pavlem Bobkem

Pavel Bobek se stal učitelem v Anglii. V Londýně učil na oceňované veřejné škole v přistěhovalecké čtvrti. Aktuálně působí v Praze na ZŠ Solidarita. Je členem Otevřena a Učitelské platformy. Věnuje se zejména popularizaci výzkumu ve vzdělávání a jeho implikacím pro každodenní učitelskou praxi. V roce 2022 byl jedním z finalistů soutěže Global Teacher Prize Czech Republic. Je autorem připravované knihy Učitelství jako řemeslo.